Recently, I came across a paper by the great historian, and philosopher of technology, Lewis Mumford, titled ‘Authoritarian and Democratic Technics’ (ADT). Mumford, who was an expert on cities and architecture, publishing the monumental The City in History in 1961, had a unique insight into the way that technics operated in an urban environment. His essay is concerned with how technical systems, from ancient times to today, have the propensity to enable or resist authoritarianism. As he writes:

My thesis, to put it bluntly, is that from late neolithic times in the Near East, right down to our own day, two technologies have recurrently existed side by side: one authoritarian, the other democratic, the first system-centered, immensely powerful, but inherently unstable, the other man-centered, relatively weak, but resourceful and durable (ADT, 2).

He claims that, at the time of his writing (1964), we were at a technological crossroads. If we continued down the path we were on, we may end up in an authoritarian dystopia enabled by a self-regulating cybernetic system:

If I am right, we are now rapidly approaching a point at which, unless we radically alter our present course, our surviving democratic technics will be completely suppressed or supplanted, so that every residual autonomy will be wiped out, or will be permitted only as a playful device of government, like national ballotting for already chosen leaders in totalitarian countries (ibid.)

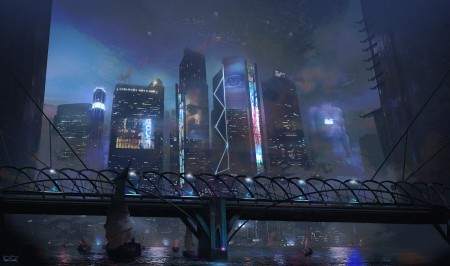

This statement immediately brought to mind images of a cyberpunk future. Giant city sprawls run by shadowy megacorporations. High-tech low-lives and posthuman augmentation… Mumford’s idea in itself isn’t a particularly novel one – thinkers have been warning about the dangers of technology for as long as technology has existed – but his claim that certain technical systems throughout history have been inherently authoritarian or inherently democratic got me thinking. If cyberpunk represented the epitome of system-centred authoritarian technics, what would the world look like if we took the other fork in the path?

The End of Cyberpunk?

Back in 2018 I wrote two articles on the origins and subsequent development of the cyberpunk aesthetic. The first looked at how the style and mentality behind the movement arose out of the economic boom and subsequent stagnation that took place in Japan in the 80s:

What had starkly affected this vision, along with the general pessimism towards the future caused by neoliberalism, was a kind of determinism about the influence of a rising Japanese economy as a threat to the America-led world order. Early cyberpunk was awash with neon lights and futuristic electronics, with Japanese signs adorning the front of every shop window. This is largely to do with the fact that in the 80s, Japan was seen as the world’s fastest rising power. The Japanese car industry was surpassing America’s, they were dominating the global electronics industry, and even buying up New York City landmarks. Some commentators had started to argue that the Japanese economy could well surpass the US economy in coming years, creating a new world superpower on a tiny island, and conjuring up images of a claustrophobic overpopulated neo-Japan not too dissimilar to that described in Neuromancer.

© Liam Wong – https://www.liamwong.com

The second article focused on how the cyberpunk aesthetic had pervaded reality to the point where parts of the world, especially in East Asia, were now starting to move beyond cyberpunk and onto something new. Here I focused on how South Korea, where I was living at the time, was shaking off the shackles of the cyberpunk futurism that Japan was still laden with. To me, it seemed that Japan’s idea of the future, or at least the future visions Japan had inspired in the 80s and 90s, had got stuck in the past:

Japan has therefore been haunted by a future left to it during a time of prosperity which is now long gone, whereas Seoul, and many other newer Asian cities are not limited by the same constraints. They are picking up their visions of the future from where Japan left off.

I called Seoul Cyberpunk 2.0 because, although there were elements of the way the city was developing that were moving beyond the tired cyberpunk aesthetic, it seemed to me that much of the city’s urban development was rooted in the same ideals that had made Japan (and other cities like Hong Kong) the inspiration for cyberpunk back in the 80s. However, despite the romanticised (and perhaps orientalist) vision of a neon lit urban sprawl, we must remember that cyberpunk was, and still is, a dystopian vision; an image of the future we want to try and avoid. But if that’s the case, then what kind of future should be we be working towards?

Songdo and the Future of Smart Cities

Not too far from Seoul, on the west coast of the Korean peninsula, there’s been an ambitious project that aims to create a new, environmentally friendly, and sustainable city that solves many of the pressing issues currently facing megacities like Seoul today. That city is Songdo. As Kaley Overstreet writes for Archdaily, Songdo was envisioned as a “completely sustainable, high-tech city, that would plan for a future without cars, without pollution, and without overcrowded spaces. It was essentially a utopia that offered everything that Seoul didn’t”.

Initiated by the Korean government in the late 90s with the first stage of development being completed in 2015, Songdo aimed at becoming the world’s first fully functioning and liveable smart city. And to accomplish this goal some of the world’s most advanced urban technologies were utilised:

The streets that connect the district are lined with sensors that measure energy use and traffic flow as a means of quantifying sustainability to support its highest concentration of LEED-certified projects in the world. Songdo also features a massive seaside park outfitted with self-sustaining irrigation systems to provide ample public space. At the level of individual residents, trash tubes take garbage away to a central plant where it is automatically sorted into recyclables and waste to be burned. Even homes are operated by cellphone apps that control everything from heating and air conditioning, to artificial light levels.

However, despite all the forward-thinking tech, Songdo is still stuck in the past when it comes to certain key issues. Perhaps most importantly, the city is designed for and built around cars with large multi-lane roads connecting the city in a grid system. Similarly, the journey to Seoul, just 30km away, takes an hour and a half by subway. Not exactly ideal for an eco-friendly city of the future.

There are also the huge issues surrounding surveillance and privacy. Every aspect of the city, from the street lamps to the dishwashers, is connected by a centralised data collection system, or “Integrated Operations Centre,” where data from the thousands of censors across the city are processed and monitored in real time. Some have even gone so far as to say that, due to the inevitable increasing reach of companies like Google into city infrastructure, the smart city will destroy democracy.

This kind of thinking certainly rings true with Mumford’s warning about authoritarian technics: “Through mechanization, automation, cybernetic direction, this authoritarian technics has as last successfully overcome its most serious weakness: its original dependence upon resistant, sometime actively disobedient servo-mechanisms, still human enough to harbor purposes that do not always coincide with those of the system” (ADT, 5). In other words, authoritarian technics has started to succeed by suppressing the conditions for the possibility of resistance, in this case through encroachment on, and control of, both private and public life.

So, despite the fact that Songdo may be the most technologically integrated city in the world, and some these developments may well pave the way for an environmentally sustainable future, it seems there are many aspects of the city that haven’t moved beyond the dystopian sensibilities of cyberpunk. As Overstreet continues: “What the designers and planners of Songdo should have done was design around the perspective and needs of a human being first with technology acting as the supplement, instead of designing for technology, with humans being just in the peripheral.” So maybe what we need is something different. Something greener. Something more human. Something more natural. Maybe what we need is solarpunk.

Solarpunk Futures

At its core, solarpunk is the ecological antidote to cyberpunk. It’s a speculative movement that traverses literature, art, design, and architecture to imagine a world where human beings live in harmony with nature, but in a way that embraces developments in modern eco-friendly technology. In other words, solarpunk imagines how technological advancements can positively respond to the challenges we face in the Anthropocene. As Adam Flynn wrote in 2014’s Solarpunk: Notes toward a manifesto[1]:

Solarpunk is about finding ways to make life more wonderful for us right now, and more importantly for the generations that follow us – i.e., extending human life at the species level, rather than individually. Our future must involve repurposing and creating new things from what we already have (instead of 20th century “destroy it all and build something completely different” modernism). Our futurism is not nihilistic like cyberpunk and it avoids steampunk’s potentially quasi-reactionary tendencies: it is about ingenuity, generativity, independence, and community.

So, where cyberpunk’s nihilistic dystopian vision has run out of steam, and even the current batch of smart cities fall prey to surveillance capitalism, solarpunk aims to take the mantle and create a new conception of the future; a “future with a human face and dirt behind its ears.”

Indeed, in the last few weeks, there seems to have been a renewed buzz on the internet around the idea of solarpunk. Much of the buzz was spurred from this tweet from Stephen Magee which received almost 60k retweets (at time of writing). Here the utopian reconnection with nature, albeit mediated through technology, seems to act as a perfect depiction Mumford’s ‘democratic technics’:

What I would call democratic technics is the small scale method of production, resting mainly on human skill and animal energy but always, even when employing machines, remaining under the active direction of the craftsman or the farmer, each group developing its own gifts, through appropriate arts and social ceremonies, as well as making discreet use of the gifts of nature (ADT, 2-3).

But it’s not just twee Ghibli-esque cartoons that solarpunk communities are pushing. As Flynn writes: “yes there’s a -punk there, and not just because it’s become a trendy suffix. There’s an oppositional quality to solarpunk, but it’s an opposition that begins with infrastructure as a form of resistance.”

Green, sustainable infrastructure as a form of resistance. Technical systems decoupled from the ‘authoritarian technics’ that Mumford warns us about. The embracing of the natural and the technical. This idea is where the solarpunk vision really comes into its own. In fact, since its conception over 10 years ago, there have been a whole host of substantial projects in architecture, urban design, and the green energy sector that have solarpunk ideals at their core.

One of the most striking, and one of my personal favourite solarpunk inspired designs, was Vincent Callebaut Architectures’ proposal for the new roof of the Notre-Dame Cathedral after the fire in 2019. As they write:

This powerful fire has awakened our dystopian imagination and somewhat echoed the church’s current identify crisis, as well as the environmental challenges we are facing through climate change … We advocate for an exemplary project in ecological engineering that feels true to its time and avoids a pastiche architecture that turns the city into an open-air museum … Circular economy, renewable energies, inclusive social innovation, urban agriculture, protection of biodiversity, without forgetting beauty and spiritual elevation: our reconstruction project feeds on such values to deliver a deep, conscious meaning.

Of course, this was only a speculative plan; the Notre-Dame spire is currently being reconstructed identically to original. But there are other projects that have taken on a life of their own.

Verne Global, a tech company that runs a data centre services in Iceland which, is powered by 100% renewable energy. The company’s CTO, Tate Cantrell, claims that the company’s MO was inspired by the solarpunk movement: “The solarpunk ethos embraces technology that disappears into the environment, and technology powered by renewable energy is a literal part of the circular economy – one that eliminates waste through the continual use of resources. This synergy makes renewable energy a very real manifestation of a solarpunk future.”

Similarly, Canadian firm Carbon Upcycling Technologies (CUT) is another organisation that is harnessing solarpunk to get communicate its vision. As the BBC wrote in August: “[CUT]’s reactor technology allows material to be broken down and CO2 absorbed, creating enhanced concrete additives. … In 2020, CUT launched a consumer brand, Expedition Air, selling products like paintings and T-shirts made from carbon-captured material. It is a move rooted in solarpunk and is based on an Artist in Residence programme.”

Examples like these, along with many more in a whole variety of different fields, have become more and more common in recent years. Solarpunk’s influence, whether explicitly or implicitly, is starting to make an impact. Now, these examples are all fairly small scale (and that in itself is certainly in-line with solarpunk’s DIY ethos) but if we want to look at citywide implementation we need to travel back to the East. Although cities such as Songdo have started on the right path, the tropical city state of Singapore has become visual embodiment of the solarpunk aesthetic, and certain aspects of the ideology in general.

Singapore: Solarpunk Utopia?

For years now, Singapore has been at the forefront of the implementation of green tech in architecture and urban design. When looking at some of the recent architectural projects completed in the city it’s easy to see why. Take Sadfie Architects’ Jewel Changi Airport for example:

The giant circular waterfall in the middle of the plaza is undeniably beautiful, but it’s the seamless integration of technology, humanity, and plant life, that make the airport truly unique. Changi might be one of the only airports in the world that could be considered a tourist attraction in its own right.

Then there are structures like the Gardens by the Bay, completed in 2012, which would be at home in any artists depiction of a solarpunk future. The gardens contain a host of green tech that aims to capture Singapore’s ‘City in a Garden’ ethos. The Flower Dome “replicates the cool-dry climate of regions like California and South Africa, and boasts more than 32,000 plants comprising some 160 species, cultivars and varieties”. Whereas the misty Cloud Forest Dome, with its 35-metre tall “Cloud Mountain”, covered in orchids, ferns and bromeliads and containing a spectacular 30-metre-tall indoor waterfall.

Perhaps the most striking and recognisable landmark in Singapore are the distinctive ‘Supertrees’. These 25 to 50-metre-tall structures are essentially vertical gardens that collect rainwater, generate solar power and act as venting ducts for the park’s conservatories. Indeed, in 2021 Singapore topped the Smart City Index, which defines a smart city as “an urban setting that applies technology to enhance the benefits and diminish the shortcomings of urbanization for its citizens”. If solarpunk is about providing real world solutions to some of the problems modern cities are facing in the wake of climate change then it’s difficult to deny Singapore’s significance.

However, although the city state is very progressive in terms of its green aesthetic vision, its politics as a whole are certainly not in line with the solarpunk ethos. Singapore’s government has often been described as authoritarian and anti-democratic by a variety of different measures. Indeed, despite topping the Smart City Index, Singapore often finds itself towards the bottom of the Press Freedom Index: “Last year, it took the 151th spot out of 180 countries – and the authorities are infamous for wielding legal threats against journalists and publications.” And this lack of freedom often extends to other parts of civil society, as The Harvard Review notes:

although Lee Kuan Yew’s reign ended almost 25 years ago, Singapore retains much of its founder’s authoritarian influence through both the PAP and the current presidency of Lee Hsien Loong, Lee Kuan Yew’s son. Singapore today is still fundamentally undemocratic.

Democracy, as NYU political scientist Adam Przeworski has put it, is a system “in which incumbents lose elections and leave office if they do.” More theoretically, the disparity between the two countries can be understood in the context of Freedom House’s Freedom in the World rankings, which track the status of political rights and civil liberties, two significant indicators of democracy, in every country in the world. While South Korea scored 2 on the 1-7 scale in both political rights and civil liberties, placing it firmly in the “Free” category, Singapore was ranked as only a 4 in each category, giving it the label of only “Partly Free.”

So, despite its solarpunk aesthetic, Singapore certainly falls short in terms of the collaborative, bottom up ideology that is at solarpunk’s core. Nevertheless, what Singapore shows is that these advanced green technologies can be integrated into contemporary city life; they can provide real world solutions to some of the problems modern cities are facing in the wake of climate change. WIth a few tweaks to the political structure, other cities could build off of Singapore’s green model, especially when it comes to architecture and urban design.

Solarpunk and Democratic Technics

And this distinction brings us back to Mumford. Towards the end of his essay he makes a statement that gets to the heart of why solarpunk can provide a counter to authoritarian technical regimes:

What I wish to do is to persuade those who are concerned with maintaining democratic institutions to see that their constructive efforts must include technology itself. There, too, we must return to the human center. We must challenge this authoritarian system that has given to an underdimensioned ideology and technology the authority that belongs to the human personality. I repeat: life cannot be delegated (ADT, 7).

Life cannot be delegated; it must be integrated. Solarpunk is not just about beautiful green futuristic cityscapes, it is about projecting an image of the future free from authoritarian technics. It’s not about rejecting technology, but embracing the connection between man, technology, and nature to imagine how we might want to live. As Mumford continues:

There are large areas of technology that can be redeemed by the democratic process, once we have overcome the infantile compulsions and automatisms that now threaten to cancel out our real gains. The very leisure that the machine now gives in advanced countries can be profitably used, not for further commitment to still other kinds of machine, furnishing automatic recreation, but by doing significant forms of work, unprofitable or technically impossible under mass production: work dependent upon special skill, knowledge, aesthetic sense (ADT, 8).

So, in a world still reeling from the pandemic, where the seeming inevitability of climate catastrophe has led to new forms of mental illness, solarpunk embodies the kind of change we need to see, and provides a realistic way of achieving it. It is a mentality that seeks to free technology from the grips of the automatic and authoritarian. It is a movement that embodies the ethos of democratic technics. Put most simply, it is a movement full of hope. And for this reason, it’s a movement that should be taken seriously.

[1] For a more detailed timeline of Solarpunk’s timeline check out Solarpunk: A Reference Guide.

Pingback: From Cyberpunk to Solarpunk: Technics and the Cities of the Future – Snapzu Lifestyle

sorry little off topic :

“like national ballotting for already chosen leaders in totalitarian countries”

1. there are two corporations which americans call parties.

2. plot on graph, difference of votes between presidential candidates in last 50 years in US elections..

3. are already chosen leaders worse in totalitarian countries or in democratic countries ? ( i understand )

LikeLike

Pingback: Is the future ‘solarpunk’? – everything alana

Pingback: Almere: The First Solarpunk City? | Blue Labyrinths

Pingback: Cyber-Solar-Lunar𝘗𝘶𝘯𝘬 | Solarpunk Station

Pingback: What is Solarpunk? The End of the World After the Revolution · BG · berlinergazette.de · EN|DE

Pingback: Solarpunk as Pharmakon: The End of the World After the Revolution · BG · berlinergazette.de · EN|DE

Pingback: What Is Solarpunk? | Blue Labyrinths

Pingback: Solarpunk als Pharmakon: Eine neue Welt aus den Ruinen der alten aufbauen – 🏴 Anarchist Federation