Leopold Bloom is the fictional hero of Joyce’s Ulysses but it was Paul Léon who embodied heroic qualities for real and the story of their friendship was first recorded by his wife, Lucie, in an account that has been out of print for three quarters of a century. It is reproduced in James Joyce and Paul L. Léon: The Story of a Friendship’ Revisited, edited by three people: Alexis Léon, the late son of Paul and Lucie; Alexis’s widow Anna Maria Léon; and Luca Crispi, a renowned Joyce scholar. Lucie’s account is one part of the book’s scholarly and heartfelt celebration of Paul Leon’s life. The longest section consists of previously unpublished letters, achingly sad, written by Paul to his wife from Drancy and Compiègne before he was sent to Auschwitz and murdered en route from there to Birkenau in April 1942.

To return briefly to the fictitious, Leopold Bloom is presented as the son of a Hungarian Jew, Rudolf Virág, an immigrant in Ireland where he changed his name and religion and, in sorrow after the death of his Catholic wife, committed suicide. Joyce’s characterization of Leopold Bloom and his Irish-Jewish identity, of which his father’s history is one facet, evolved after the author settled in Trieste after leaving Ireland in 1904; the city’s Jewish community and his many Jewish friends and acquaintances there – including Ettore Schmitz who may well have been a model for Bloom – are documented in John McCourt’s The Years of Bloom. The centrality, more broadly, of Jewishness in Joyce’s consciousness is the subject of Neil R. Davidson’s James Joyce, Ulysses, and the Construction of Jewish Identity.

Joyce and his family settled in Paris in 1920 and in the following year Paul and Lucie Léon, also moved there, setting up home in the city where they would spend the rest of their lives. Paul, born in 1893 in St Petersburg, Russia, had been writing a dissertation at Moscow University on the anarchist Bakunin before departing with his family after the Bolshevik Revolution in 1918. He first met Joyce ten years later and by this time the Irish writer was famous as the author of Ulysses and engaged in publishing fragments of what would become Finnegans Wake. Paul became Joyce’s most trusted friend in the 1930s and provided crucial help with his writing, working as his secretary and effectively becoming his literary agent – while insisting on not receiving any payment – as well as pursuing his own scholarly interests. It is Crispi’s considered opinion that without Paul’s friendship and help Finnegans Wake would never have been completed. This is an important assessment, giving Paul the recognition he deserves but which has not always been acknowledged in the voluminous Joyce scholarship.

By the 1930s, Joyce may have been a world-famous author but his life was beset with personal and professional difficulties. Completing Finnegans Wake and getting it into print, plus endless copyright issues over Ulysses, had to contend with dealing with the deteriorating mental state of his daughter, Lucia, and the precarious condition of his own eyesight. He was forty-seven when he first met Paul, eleven years younger, and the friendship that developed between the Irish and the Russian émigré is evoked for the reader in the details of Lucie’s memories of their time together. Their regular, usually daily meetings would begin with light taps on the door of the Léons’ apartment and Joyce asking if he was at home: then, “…they would begin pouring over proofs again, or else wander off to the corner bistro for an apéritif and a chat. Or they might discuss some current problem, Finnish royalties or the health of Joyce’s daughter Lucia.” Paul told his wife that Joyce had spent three-quarters of his income on doctors and sanatoriums for his daughter, something he came to know through his handling of his friend’s complex financial affairs.

The unforced intimacy that evolved through their companionship comes across with conviction in both Lucie’s account and Luca Crispi’s story of her memoir’s publication. It is a story that sheds new light on how Paul identified as a Jew though, like his wife, he did not practice or believe in Judaism and felt more committed to the Gospels. When, however, Jews had to declare themselves in Paris to the authorities, he undertook the wearing of a yellow star as an act of responsibility: “My husband never concealed his origins” (underlining “never”), wrote Lucie in a letter to the Joyce scholar, Joseph Slocum, who became her personal friend. They first met in New York in 1947 and Slocum organized a public talk by her about her husband’s friendship with Joyce and went on to help with the eventual publication of her memoir. When an English newspaper printed a misleading account of Joyce and Paul, she wrote to its editor expressing her annoyance at having her husband described as “Joyce’s Jewish helper”. Stalwartly affirming her husband’s Jewishness and his devotion to Joyce, she points out that the famous writer had other friends who were not Jews and who also helped him: “I have not noted they have ever been referred to as Protestant, Catholic, Anglican, Methodist or Presbyterian.”

After the Nazis invaded France in May 1940, the Léon family sought refuge away from the capital and headed in June to the village of Saint-Gérand-le-Puy; Joyce and his wife had been there since February. It was here that the Léons made the most fateful of decisions – it would cost Paul his life – choosing to leave Vichy France and return to Paris. “It seemed to be the only thing to do”, she recalled, for everything they had was in the capital, and “our funds had dwindled to nothing”. Many of the 175,000 Jews who lived or had found refuge in Paris joined others in fleeing the city when the German army arrived in May 1940 but many, unaware of the full extent of Nazi intentions, returned to the city after the armistice was signed the following month.

Back in Paris, Paul attended to Joyce’s affairs as much as he could. He collected his and Joyce’s private correspondence and deposited it with the city’s Irish Legation but then, in January 1941, came the unexpected news that Joyce had died in Zurich of a perforated ulcer. Paul was devastated and Lucie recalled that for days he could not bring himself to speak about it, initially refusing to write about his deceased friend. What he did do, when the landlord of Joyce’s apartment put its content up for sale in an auction, was buy back most of what he considered worthwhile (with a fund provided by his brother) – eventually they found their way back to Mrs. Joyce – and, risking arrest, made two trips to the apartment with a pushcart to rescue the Joyce’s family books, manuscripts and correspondence (now part of the Joyce collection at University of Buffalo).

In August 1941, Paul was arrested and interned, first in the Drancy transit camp, administered by the French police at that time, before being moved in December to another camp further north of Paris in Compiègne. From these places he wrote some fifty letters to Lucie, the last on 26 March 1942, the day before he was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Nearly all of them were smuggled out of the camps, probably through the Red Cross and/or simple bribery and they appear in this book in their original French and in English translations, transcribed and edited by Mary Gallagher. She rightly draws attention to their enduring value as a historical document and notes how their form changes as Paul’s initial resoluteness gives way to a growing realization of his existential plight. Reading the letters is distressing, especially those at the end of November, when his anguish becomes palpable, and the final one on the eve of his departure from France. “We’ve been counted and tomorrow we leave – I don’t know where we are going or how”, it begins, before Lucie is asked “to remember all my tender love for you and Alexis” and a farewell extended “to all our friends as well, the ones who turned out to be true friends. I love them all.” He accepts his fate while stressing that the most important thing is for her to know “that I love you as much as I did twenty years ago and that – if I don’t see you again – it is you that I shall love forever.”

It is possible, says Crispi, that Paul spent more time with Joyce than anyone outside of his immediate family at any period of his life. Only now, with a book that makes a valuable contribution to Joyce scholarship in its own right, is testimony registered to a man who personified in his real life the humanism and politeness of the heart that the fictional hero of Ulysses was endowed with by his creator.

Bibliography

Davidson, N. R. (1998). James Joyce, Ulysses, and the Construction of Jewish Identity: Culture, Biography, and “the Jew” in Modernist Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Joyce, J. (2000). Finnegans Wake. London: Penguin.

Joyce, J. (2000). Ulysses. London: Penguin

Léon, A., Léon, A. M. & Crispi, L. (2022). James Joyce and Paul L. Léon: The Story of a Friendship’ Revisited. London: Bloomsbury.

McCourt, J. (2000). The Years of Bloom: James Joyce in Trieste, 1904-1920. Dublin: Lilliput Press.

Sean Sheehan is the author of Jack’s World (Cork University Press, 2007), ‘Ulysses’: A Reader’s Guide (Bloomsbury 2009), and Žižek: A Guide for the Perplexed (Bloomsbury, 2012). He lives in London and West Cork and is currently writing a new book about Žižek, to be published next year.

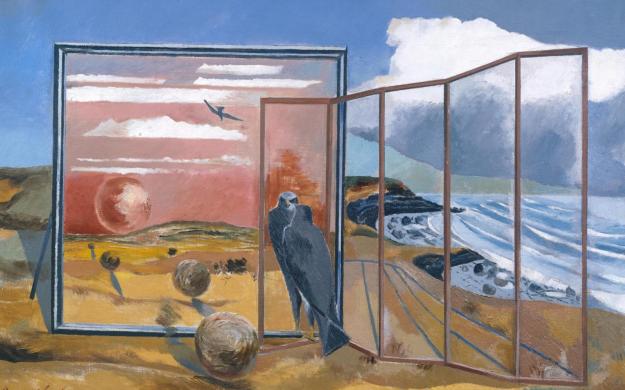

Credit for cover: © Paul Nash