In the 2007 book Bioaesthetics philosopher and teacher of Aesthetics Pietro Montani writes about the increasing disempowerment of the external world as a source of forms where “a digital image no longer has any need to draw on the visible world to produce a mimesis” and “the self-referentiality of representation is therefore growing, and exponentially so.” Considering the history of landscape representation in visual arts — above all, cinema — as a journey in stages, one could say that an early depiction of the natural landscape as hostile has been replaced, in the contemporary era, by a depiction of the landscape as a complete (and visible) externalization of the ideal inner world. This outward movement, which projects a set of values toward the tangible “physiological” world is what causes, as Montani explains, “a direct hold by power on the strictly biological dimension of life.”

One cannot disregard the formulations of French sociologist Jean Baudrillard, a philosopher — who understood how much the forma mentis of human beings could be influenced by the cinema interface — when talking about virtual (as in “Other”) simulacra. The 2017 film The Florida Project by Sean Baker is a perfect example to help one grasp the application of Montani’s theories.

Shot on the outskirts of Orlando, Florida, where the majestic enchanted castle of Walt Disney’s huge theme park rises, Baker’s film chronicles the very deep disconnect between the utopia promoted by Disney World and the decay of the surrounding areas, left to themselves as wrecks and far removed from the wealth erupting from the park’s streets. Indeed, the only way to try to profit from the fairy world that lies just a few kilometers away consists of a disturbing operation: the construction of dingy, depressing, and poorly frequented motels, which, thanks to a tint of pink paint and evocative names such as “Magic Castle” or “Futureland,” aim to attract hapless tourists looking for a cheaper Plan B aside from sleeping inside the park. How to do this? By recreating Disney’s imagery, in a place that’s close geographically and still so estranged from the actual park.

Within this scenario, stories unfold of the characters who inhabit the Magic Castle: first and foremost, little Moonee (6 years old) who lives in one of the motel rooms with her young mother Halley. In the film, the children’s point of view is incredibly important: exposed to situations of degradation, they live their childhood surrounded by a bitter and ruthless adult world, which nevertheless retains the appearance of an extremely infantilized world.

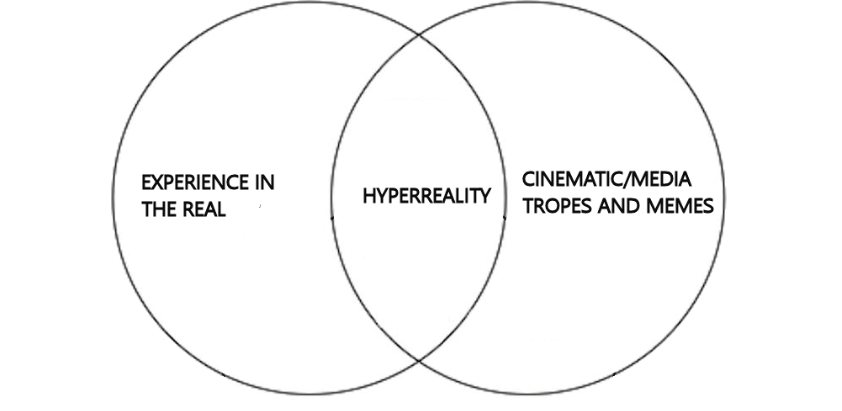

That of The Florida Project is a landscape forced to bend to the imaginary, and not only that: it is a landscape that has introjected the capitalist system behind the dreamlike surface of the Disney fairy tale, and has now surpassed it to turn itself upside down altogether. From selling gadgets to building colorful hotels, leaning on the echo of Mickey’s world is now the only way to survive outside the gates of Orlando Park. The children in Baker’s film grow up in a simulacral world, a dimension where the real world draws on the “virtual” world of cartoons, in a reflecting game between imagination and reality. That’s what Pietro Montani refers to with the term an-aesthetization: the aestheticization of politics as one of the salient dynamics of biopower which, according to the philosopher, has intensified and capillarized in the post-modern era. The consequences of that, according to Montani, seriously invest the mechanisms of collective living, generating “a carefree sensibility, an emptying of its meaning that perverts it, with ephemeral or lasting hedonistic reward, into pure sensation or sensationalism.” Something of which “the universe of technically produced images is the great workshop for.” These are, Montani continues, “‘hyperinvested’ practices of commodification of segments of experience, which tend to surrogate, without residue, political judgment.”

Baudrillard refers to this with the term “hyperreal”: the non-distinction between reality and its signifier. ”Abolition of the real world not by violent destruction, but by its elevation to the force of model.” When he speaks about the “exauthorisation” of the external world, Montani warns of its progressive loss of authority and rather insists on the great autonomy gained by the Imaginary. British author and film theorist Daniel Fraser clarifies once and for all this dreaded newly acquired independence. About Sean Baker’s film, he writes:

“Just like that, the film’s space is a distortion of the hyperreal, accelerated, capitalist ideology of Disney World, but also of the everyday landscape of capitalism. […] Something sinister lurks in the landscape of The Florida Project: the existence of a space that not only serves capitalist reproduction, but in which any potential resistance to its machinations is neutralized […] The landscape of the film thus presents a picture (if that were possible) more pessimistic than that of the Disney world. Here, the capitalist ideological myth has reached such a level of ruin that it neutralizes any intervention that might seek to explode the conditions of this nightmare.”

The landscape in The Florida Project is a space where power has turned its back on its inhabitants: it has grown, thriving, beyond the need of its own failed capitalist purpose. Outlining an equally — if not more — fearful portrait of the same power dynamics, the 2020 documentary Jasper Mall by Bradford Thomason and Brett Whitcomb depicts the same dynamic. The two filmmakers film the stories of a group of people inhabiting a mall in Jasper, Alabama, that is now near to closure. For each of these people, Jasper Mall fills a different role and has a different emotional significance: the security guard remembers it as the place where his love affair with his wife started; a group of elderly people use it as a meeting place where play with cards; for a young couple, it is a place to spend their last moments together before they both leave for college.

Everyone, however, agrees on one thing: the mall resembles a community, a town where everyone knows each other as neighbors. Indeed, watching the stores close one after another, it looks like the spectator’s witnessing the gentrification of a neighborhood that — instead of transforming an area from proletarian to bourgeois — empties each store of its identity, leaving in its place a grey empty hole condemned to dust. — and forcing vendors to accept the reality of online shopping (the distribution of the film by Amazon Prime Video is more than ironic).

Here, again, the capitalist paradox occurs through the mall’s acquisition of autonomy. The mall is the highest example of a non-place, somewhere in which the very capital is inscribed. The closing of the Jasper Mall thus reveals a very strong identity parenthesis within a place that apparently has no connection with life outside of it.

The operation carried out by the two directors is subtle and frightening: the spectator is not saddened by the shopkeepers being forced to close their stores, but by the imminent death of the mall as an entity on its own, linked to memories that one does not want to let go of. This kind of connection to memories is also elaborated by Montani, using the term coined “mnemonics” coined by the philosopher Bernard Stiegler. For the philosopher, if anthropogenesis and technogenesis coincide without residue, the movement that prolongs man into his inorganic prostheses has effects on the entire organization of his experience and culture, beginning with the cardinal role that Stiegler attributes to externalized memories (literally: “mnemotechniques”). For Stiegler, the mnemonics phenomenon is interrogated “in relation to its role in the experience of time […] and in the formation of an individual consciousness that is intimately connected to that experience.”

Indeed, according to Stiegler, the human tendency to externalize one’s memory in a cultural-technical framework has given rise to a third pole of mnemonic aggregation, beyond biological and individual memory. And it is exactly with the concept of memories that the two directors of Jasper Mall are working: for Thomason and Whitcomb, the film is nothing but a nostalgic process. During their childhood and adolescence — the filmmakers reveal — malls were spaces where to spent whole afternoons together with their peers. “When we got old enough to go there on our own, [our parents] would take us there, and we would spend the whole day there, with friends,” Thomason says. “Brett and I would both hang out at BayBrook Mall, or The Almeda Mall (Texas) […] at the Arcade, buying CDs at Sam Goodie’s, eating pizza in the food court, and looking at the new Reebok Pumps I wished I had before school started.” For them — and for so many other people around the world — looking at an abandoned mall is like finding old previously owned toys in the basement, being aware that they will no longer be needed by anyone else, and that they are now doomed to be empty plastic objects forever. What Jasper Mall highlights is a dystopian scenario that’s impossible to escape: the humanization of a commercial activity becoming an entity surrounded by affection: something we wish we could never forget. Admittedly, the mall is a surrogate for reality, yet seeing photographs of the mall in the 1980s — when parking lots were full and all the aisles crowded — will inevitably cause a sense of deep and intense nostalgia.

One thus runs into, just as in the anti-fairy-tale world of The Florida Project, the inability of a transductive relationship between political judgment and an un-elaborate feeling of familiarity or nostalgia: this is how human beings have been able to fall in love with capitalism. And just like Montani suggests, the risk of atrophying human perception has to be overcome by getting to know something he calls “ethics of forms.”

In the article On Devirtualization — how the physical contorts to satisfy the virtual, the author and media theorist Jam Ritger hypothesizes the emergence of a phenomenon he calls “devirtualization”:

Instead of defining our world through a proximity of layered meanings (structuralism), we have begun to define our world through signs, symbols, and simulacra. In short: the virtual has colonized the real. I believe this is an accurate assessment of life in the 21st century, yet the construction of tall luxury skyscrapers continues with little or no change. If the practical value of these structures has been outweighed by the sign value of their luxury, then who is the consumer? The answer is that all those apartments were not and are not built to house human beings, but to house investments in a practice known as “money parking.”

One of the most illuminating examples provided by Ritger is the design of skate parks. Appeared to translate surfing from a water sport to a land sport to make up for the absence of waves during a dry season, skating moved to suburban landscapes, where skateboarders used sidewalks, stairways, and industrial architecture to practice their sport. From there, the design of skateparks produced wonderful objects such as benches rising out of the ground and specific paths within parks in order to serve routes for the tricks. The proliferation and popularity of skateparks have then caused urban planners to introduce the aesthetics of pre-fabricated parks into the Zeitgeist, transforming areas of cities into “devirtualized” spaces, where the architectural tactic known as “skatestoppers” is prevalent: small metal knobs that limit the usefulness of trick benches, empty spaces or bricks that make it impossible to play the sport in parks. According to Ritger, “in this case, the post-gentrified landscape devirtualizes skate design out of its experimentation and expression, reducing it to mere aesthetics.”

In contrast to the aforementioned case, where initially “livable” and “consumable” places are transformed into empty shells with no more utility, the hyperreal landscapes of The Florida Project and Jasper Mall are crossed by characters who literally inhabit between the creases and folds of capitalism. But is educating ourselves to an “ethics of forms” really possible? What will happen if we fail to notice the power structures behind the landscape we inhabit every day? After all, that is precisely the “Florida Project” evoked by the title of Baker’s film. And it is the great dream of every power system: to permeate the societies it wishes to control to a point where it goes unnoticed.

Bibliography

Fraser, D. (2018). Fairy-Tale Capital: Landscape in The Florida Project. Medium.

Wake, M. (2020). Alabama Shopping Mall Subject of New Documentary Film. AL.

Ritger, J. (2020). On Devirtualization, How the Physical Contorts to Satisfy the Virtual. Punctr.Art.

Montani, P. (2007). Bioestetica. Senso Comune, Tecnica e Arte nell’Età della Globalizzazione. Roma: Carocci.

Arianna Caserta (2001) is a writer and film theory researcher focusing on the links between cinema and internet culture. Her research areas include experimental films, teen movies, online subcultures and new media art.