Freedom is an online performance by Eva and Franco Mattes. Its setting is the infamous FPS video game Counter-Strike. Eva, as an Avatar/Soldier, roams the battlefield begging everyone she meets not to shoot her because she’s an artist doing an art piece. Her pleas are constantly ignored and the performance turns into a cycle of death. And Eva is the only victim. All players, but Eva, seem to be possessed by their Avatars. She, on the contrary, resists the Avatar, by refusing it completely. And she ends up dead.

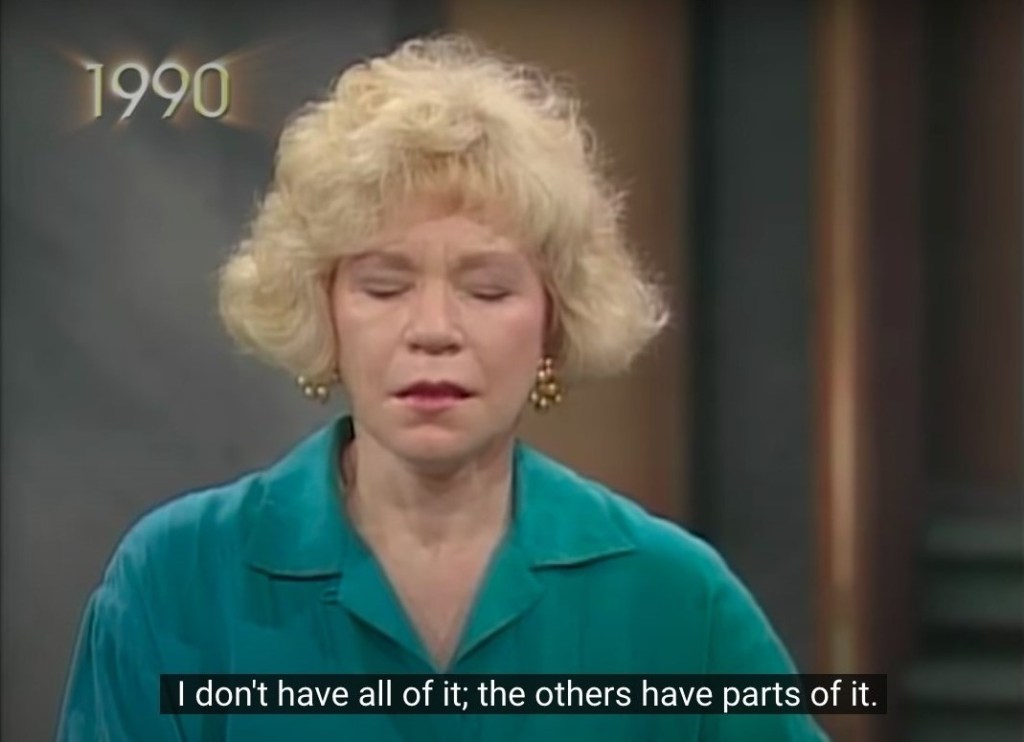

Truddi Chase Militia

In 1997 Sadie Plant declares:

The new networks suit these distributed characters so well that they might almost have been made for them. […] as though they were building circuits for themselves, inconspicuously assembling support systems for their alien lives, the technical means of emergence and survival, networks on which whatever they become can replicate, communicate, make their own ways. Cultures in which they can thrive at last.

(1997, p. 137)

Formerly known as Multiple Personality, Dissociative Identity Disorder is a mental condition characterized by the presence of two or more distinct identities or personality states that recurrently take control of the subject. Each personality (in jargon, Alter) is “a unique entity, shut off from the others. Each self has its own typical bodily gestures and facial expressions, its own particular habits, preferences, and speech patterns, and even its own pulse rate” (Shaviro, 1996). Truddi Chase, a woman who became a media case in the early 1990s, finds a way to co-exist with her 92 personalities without going crazy, by recognising each of their precise roles and functions: there is the Gatekeeper, The Buffer, The Weaver, The Interpreter, but also the Workaholic Businesswoman, the Party Girl, the Barbielike Miss Wonderful, the Catatonic, the Sophisticated, the Sewer Mouth, and many others. Together they seem to form a Militia (Truddi calls them “troops”) as they are “the result of an immense collaborative effort which involves the delegation of powers, and the coordination of numerous limited and largely autonomous functions” (Shaviro, 1996). Indeed, in Dissociative Identity Disorder, although each personality is well-defined, none is able to subsist alone and mutual proximity cannot be escaped: “each of the selves is conscious only part of the time, and none is ever directly aware of what happens to the others. Someone acts, someone else hides in terror, someone else stirs uneasily in her sleep, and yet someone else’s rage or grief is a murmur indistinctly resounding” (Shaviro, 1996). The personalities must therefore find ways to coexist by cooperating with each other, to bring about a — sometimes compact, sometimes rebellious — formation, in jargon called System, in which the body and the official identity, the woman who is Truddi Chase, become the proxy through which all personalities come to life:

the self who appears continuously to others and who serves as her legal representative in the world, is just such an empty space. She is merely a puppet or a robot, a “facade,” manipulated and ventriloquized by the other selves. She remembers nothing, and she speaks only from dictation.

(Shaviro, 1996)

Proxification

The digital field requires and implements a multiplicity of technical mediators — “They are masks, persons, avatars, routers, nodes, templates, or generic placeholders” (Steyerl, 2018, p. 73) — through which humans spread their online presence by proxy. In computer science, the term proxy denotes a type of server that acts as an intermediary between the computer and the Internet network. If my configuration involves a proxy, whatever my request is (a file, a web page, or any other available resource) the proxy will execute it for me, interposing itself between me and the network and thus becoming the only visible identity. A proxy server (just like an Alter) has specific functions: it provides anonymity while browsing, and it creates a “defense barrier” (Firewall) that acts as a filter for incoming/outgoing connections by monitoring, controlling, and modifying the internal traffic. And if it’s true that I am contained in the proxies I use (in all the routers, templates, and almost every digital surrogate) then it is a “disengaged, delegated, translated and multiplied” version of me (Latour, 1996).

Avatars, just like proxy servers, stand between the physical self and the digital world, becoming momentarily but officially us by virtue of the fiction of the “as if” (Mulvin, 2021, p. 25). Fictions have always been effective means of generating reality and they proliferate in all aspects of our lives: in patriarchal fiction, for instance, men count more than women, and a married couple is worth more than a de facto couple. In the capitalist fiction fiat money is worth more than gold and in art fiction, and in the art fiction the only credible artist is the one who’s always visible. Similarly, while gaming, we set a fiction in motion: we act as if we were the Avatar, and by doing so we create a reality in which we effectively are the Avatar. These digital bodies, however, simply act in our stead in the video game. We are bound to them because they are our delegates. This bond implies an exchange between the representative and the represented, where humans implicitly ask their proxy: Will you be my faithful delegate? And this question contemplates the possibility of betrayal.

It was recently discovered that in video games the avatar can infiltrate gamers and influence their choices and behaviour in the game. This kind of user-avatar relationship is called “Proteus effect”. More specifically, this definition refers to the phenomenon whereby the characteristics of virtual avatars can influence the in-game behaviours or attitudes of the player. For instance, it has been shown that individuals playing with taller avatars act more confidently and negotiate more aggressively, regardless of their physical height (Szolin et al., 2023a). So, the choices I make when I am my avatar-soldier are not the same as if I were my “actual self” or if I was playing as a pacifist avatar. In a way, when gaming, it is the avatar that influences me, it is the Avatar who decides. “Heiko spoke of his avatar’s resistance to completing an infamous torture quest, despite his own interest as a gamer in seeing how it played out. ‘He didn’t do it,’ he said. ‘I just could not do that quest with him and it made no sense'” (Banks, 2015). In video games we don’t merely “wear” the avatar as a mask or a costume: we engage in processes of delegation, during which the character can temporarily take a decision-making role. And not only during the game. Indeed it seems that the proteus effect can transcend the virtual environment and influence the behaviours and attitudes of individuals even outside the game, in the physical world:

Sometimes the avatar has a very tasty hairstyle. So because it is in the virtual world I try to bring it into the real world, so you kind of go to the barber shop and you just run that hairstyle, yeah. And two, take for example the clothing styles, sometimes the clothes are just nice and decent, so you just try to go out and pick some just to try and imitate the avatar.

(Anonymous Gamer, in Szolin et al., 2023b)

Avatars are leaking out of the digital world to creep into us as brand-new personalities and they are ready to inhabit the physical world through our very bodies. Then one might ask, who is the proxy now? Who is the avatar?

Avatar leak

In the essay On Technical Mediation, Bruno Latour emphasized how mediation is not only a program of actions (i.e. the series of goals, steps, and intentions), it is most of all a means of displacement which leads to the production of something or someone else. What does this mean? Let’s use the example given by the very same Latour: Saying that guns kill people is not the same as saying that people kill with guns. In the first case, I automatically define guns as agents (not tools); they are the ones who kill, and the person carrying the gun is a proxy. On the contrary, by affirming that people kill with guns, I determine guns as intermediaries for an agent (a person) to complete the action of killing. There is a third option, says Latour: what really happens in virtue of the process of mediation is the creation of a link and a new purpose that didn’t exist before and that to some degree modifies both the weapon and the human carrying it. He writes:

You are another subject because you hold the gun; the gun is another object because it has entered into a relationship with you. The gun is no longer the gun-in-the-armory or the gun-in-the-drawer or the gun-in-the-pocket, but the gun-in-your-hand, aimed at someone who is screaming. What is true of the subject, of the gunman, is as true of the object, of the gun that is held. A good citizen becomes a criminal, a bad guy becomes a worse guy; a silent gun becomes a fired gun, a new gun becomes a used gun, a sporting gun becomes a weapon. […] Neither subject or object (nor their goals) is fixed.

(Latour, 1994, p. 33)

In this union, human beings and technical mediators manifest a distributed agentivity (Latour, 1996), and the Proteus effect seems to demonstrate that such agentivity, on a purely phenomenological level, is displayed as a true autonomy of the proxy. So while Avatars offer their algorithmic bodies for us to exist in the digital world, we give them our flesh so they can exist in physical reality. And as the virtual collapses into the concrete world, Multiple Identity Systems rise everywhere and humans only stand in as mere official representatives.

In Dissociative Identity Disorder, refusing a personality might mean the death of the System, as that personality might take over and destroy all other alters. Similarly, we can’t reject our Avatars, and dismiss them as mere tools, as they are now an active part of our Identity System/existence, and they are becoming “increasingly smart. Vociferous in their declarations of life and their determination to survive” (Plant, 1997, p. 135).

Endnote

In the video documenting the online performance Freedom, at 6:42, one of the players keeps repeating “Why are you so bad, bro?” The player sounds almost amused by the killings. He may or may not be possessed by the Avatar.

Bibliography

Banks, J. (2015). Object, Me, Symbiote, Other: A Social Typology of Player-Avatar Relationships. First Monday, 20(2).

Latour, B. (1994). On Technical Mediation. Philosophy, Sociology, Genealogy, Common Knowledge, 3(2), 29-64.

Latour, B. (1996). On Interobjectivity, Mind, Culture, and Activity, 3(4), 228-245.

Mulvin, D. (2021). Proxies, The Cultural Work of Standing In. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Plant S. (1997). Zeros + Ones, Digital Women and the New Technoculture. London: Fourth Estate.

Shaviro, S. (1996). Doom Patrols. A Theoretical Fiction about Postmodernism. London: Serpent’s Tail.

Steyerl, H. (2017), Duty Free Art. Art in the Age of Planetary Civil War. London: Verso.

Szolin, K., Kuss, D. J., Nuyens, F.M., and Griffiths, M. D. (2023a). Exploring the User-Avatar Relationship in Videogames: A Systematic Review of the Proteus Effect, Human–Computer Interaction, 38(5-6), 374-399.

Szolin, K., Kuss, D. J., Nuyens, F. M., and Griffiths, M. D. (2023b). “I Am the Character, the Character Is Me”: A Thematic Analysis of the User-Avatar Relationship in Videogames. Computers in Human Behavior, 143.

The original version of this article was published in Inactual.

Arianna Ferrari is a performance maker and writer. She exhibited her projects in independent spaces, art galleries, and cultural centres, both in Europe and North America. Her works have been included in both independent (Keep it Dirty: vol. a, Punctum Books), and academic publications (An Introduction to the Phenomenology of Performance Art: Self/s, TJ Bacon, Intellect Books; ¡Mamá, de Mayor Quiero Ser un Cyborg! La Performance como Resistencia Somatopolítica, M. López, Universitat Politecnica de Valencia).