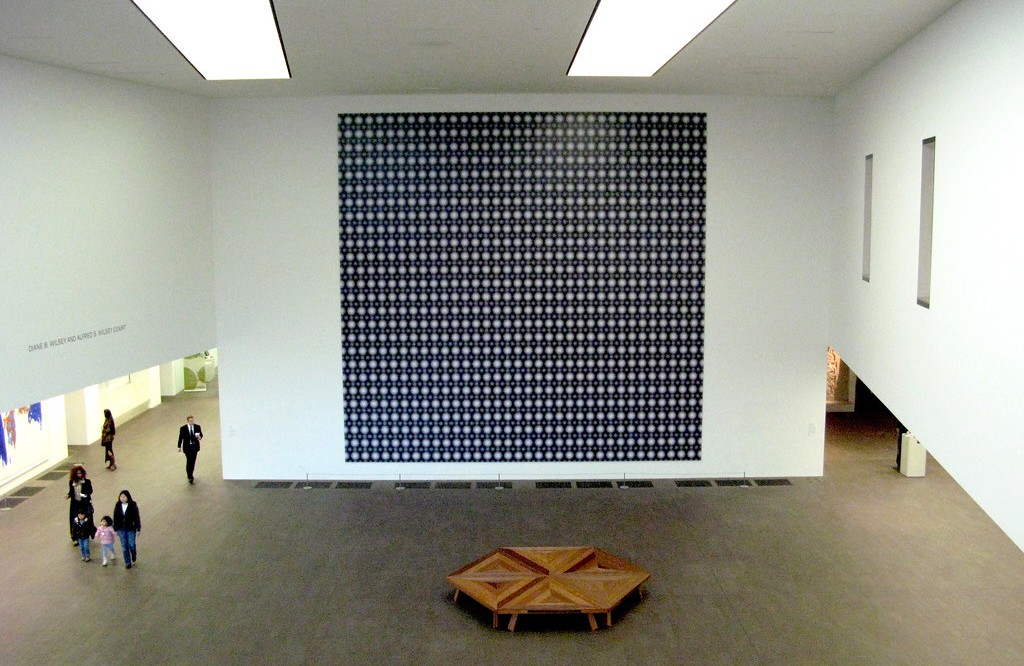

When some years ago the De Young Museum in San Francisco was preparing to reopen in a new building, the directors of the museum commissioned a work by the German artist Gerhard Richter to be displayed on the main floor of the museum. Richter produced an enormous C-print, which is displayed alone on one of the walls in the central part of the building.

The work consists of panels each repeating the same image of a molecule of iron. In his habitual modus operandi, which from the very beginning of his career was the typical melange of what is now known as “contemporary art,” e.g., gimmick, ploy, gadget, banality, etc., the artist utilized the blow-up of an image he had found in a newspaper photograph.

The curatorial card on the wall says that the work is the “largest and most significant” work commissioned by the museum and that the commission sought a work that could function as the “central focus” for museum goers. The card also says that Richter’s “lifelong interest in the aesthetics of accomplishment” found a way in this work to “explore structures” and to “change perception,” allowing “for an endless projection of meanings” onto the work’s “minimalist, yet mysterious surface.” The curatorial information concludes with the statement that a viewer will experience a “psychological and visual dilemma”.

Of course, this information consists of that kind of contemporary art theoretical vacuity, indeed of contemporary aesthetic reason tout court, which in being applicable to anything at all is in fact applicable to nothing at all – given that each and every notion is the product of a discursive prefabrication the result of which is the absence of any and all content. Furthermore, the exceedingly (and not even minimally!) banal and uneventful form and content of the work, stillborn as it is and as are the vast majority of the works which circulate in contemporary art’s regime of visibility and canon, does not lead viewers to experience a “dilemma” nor is the work a “central focus”.

If one looks directly at any portion of the work’s repeated panels and repeated images, one finds it impossible, given the particular configuration and pattern of each repeating panel, to focus. But it is not here a question of the transparent ploy – enticement – Richter used earlier in his career and which launched his “star”, the ploy which was immediately and ever thereafter swallowed hook, line, and sinker by the entire class of art world functionaries, i.e. of reproducing in paint the direct contents of a photograph with the one alteration being that Richter painted the photograph as if the original had been a blurred photograph. Of course, the entire skein – and contents – of art world production from neo-Dada to “contemporary art” has been at once intrinsically and extrinsically nothing other than the succession (“history….”) of those gimmicks and ploys which were able on the basis of nothing other than random and contingent particularities to gain access to the regime of visibility and to, thereby, constitute this regime’s art-historical, art-curatorial, and art-theoretical canon to which every faction and stratum, competing or otherwise, among the conglomerated functionaries, pay seamless obeisance. But the essential nature of this regime – of this system – is that all these gimmicks and ploys which have gained access to the regime of visibility could be randomly substituted with those gimmicks and ploys which did not gain access to the regime in question – while leaving in place all accompanying art-world discourse, commentary, and adulation – and no one would notice the difference.

But whereas one can focus without physiological discomfort (I bracket the question of aesthetic, intellectual, and affective discomfort…) on Richter’s blurred works, given that the “blur” is the already instantiated optico-perceptual foundation-image, here in relation to Richter’s C-print, it is the foundation-image itself that optically repels focus. One doesn’t experience a “dilemma”; rather, one experiences immediate physiological and optical distress. And it is not a question here of metaphor nor of a psychological distress owing to any kind of negative aesthetic judgment one might have of the work, although many viewers might well find themselves (will certainly find themselves) forming such a negative judgment, given that the work does not even rise to – and this is what marks it out as a standard, interchangeable, undifferentiated (and indifferent and indifferentiating) work of “contemporary art” – the level of incidental interest, which is to say it doesn’t even rise to the level of incidental ennui or nullity. Nor is it centrally a question here of negative judgments about both the abject nature of the habitual inflation (and stagflation…) to which curatorial reason gives itself so readily and about the ever-present art-world inflation of “monumentality” to which artists give themselves in a quest at once to outbid their own lack of imaginative and creative reason and to garner the highest commercial bids. Simply, essentially, the immediate experience of this work of Richter’s precedes and transcends all the dilemmas of aesthetic judgments and the impossibility of their universalization, precedes and transcends whatever negative feelings and negative aesthetic judgments one might have about the work, seeing in it one more instance of the aforementioned indifferentiation of contemporary art and particularly of Richter’s serial gimmicks.

All viewers of this work, universally, including all those who would form a positive judgment of the work, will experience an immediate and ineluctable sensation of physical-optic discomfort which becomes the immediate and thereby the originating function of the work. I should add that a positive judgment of Richter is one of the standard, central, and elemental shibboleths for entry into contemporary art and its discourse regime, a shibboleth pronounced universally(!) by critics, curators, theoreticians, academics, historians, and ever the more eager and submissive philosophers (see Peter Osborne’s books on contemporary art as perfect exemplars) save for Donald Kuspit whose vehement and marvelous dissent vis-a-vis Richter is but the exception proving the rule. “Ryman”, “Sherman”, “Wall”, “Hirschorn”, etc. are others among those whose ploys and gimmicks have made it through the strait gate and whose nominatives now serve as other essential passwords whether on the part of the art critical apparatchik “Left” (Buchloh, Foster, Osborne, etc.); the art-critical structuralist-formalist center (Krauss, Bois); pro-situ mandarins (Clark, etc.); neo-cynics (Groys, etc.); pop-analytics (Danto, etc.); curatorial bureaucrats (Varnadoe, etc. ); neo-contemporary “adherents” (Joselit, etc.); or even “accelerationist” “contemporanians” (e-flux, etc.).

And whether it is in another Octoberist such as Thierry de Duve or in the misapplied and, thereby, not at all deft use of Adorno’s aesthetics by J. M. Bernstein, an art-world “outsider” (and a critic of de Duve) applying to “gain entry…”, de Duve’s declaration, “Ryman and Richter are our two greatest contemporary painters” (Michael Fried would, doubtless, add Marioni) is the paramount banner and watchword of all and sundry. In short, whatever ploy or gimmick finds its way into the regime of visibility, whatever the art galleries and immediately thereafter in full automatism the art glossies place before the carriers of contemporary aesthetic “reason”, this very “placing”, and its “here” (both as offer and as reward) receives no dissent.

All of the aforementioned functionaries might squabble about everything and all and sundry, etc., but whatever has become visible (on the basis of an entirely irrational automaticity) has, henceforth, become the object of the validating and self-validating circularities and prefabrications of the discourse machine. The utterly opportunist vacuities of Hirschorn’s “leftism” and Richter’s stripe paintings, both of which make the apparatchiks, e.g., Buchloh, Foster, etc., swoon are but two among so many other possible examples.

There are, of course, those among the artists, curators, critics, historians, and theoreticians constituting the population of art world functionaries who will say that the creation of discomfort is one of the paramount, valuable, and validating features of a portion of modernist and contemporary art. Perhaps, they would cite Guy Debord’s first film, the 1952 Hurlements en Faveur de Sade, a film constituted entirely of alternating white and black screens (created with blank leaders) with a black screen of a duration of twenty-four minutes closing out the film. The film does have an accompanying voice-over soundtrack/narration in several voices of various lyrical and socio-political enunciations. Doubtless, Debord’s film from one point of view, if not more seeks to create discomfort, but the distress it might cause would be affective and/or intellectual (and not per se physiological), e.g., tedium, annoyance, indifference, a negative aesthetic judgment, “outrage”, “indignation”, or even indulgence, etc. Certainly one could also form a positive judgment of the film in a perspective deemed contestationist, transgressive, “avant-gardist”, “experimental”–or even, let us laugh, since, alas, Debord never did, e.g. ”cool”, “crazy”, “out there”, “gone”–or to use one of curatorial reason’s silliest vocables, “edgy”, and so on.

And in either case one can, perhaps, enjoy the film-script narration or even, given one’s aesthetic/historiosophical position or more aptly, conformity, the monochromatic aesthetic of which the film was and remains an inescapable representative – and copy, given that Debord’s film not only reenacted in a slightly different manner Gil Wolman’s film of the year before, L’Anti-Concept, but was precisely an instance of the poverty and indifferentiation characteristic of the then burgeoning and soon to be dominant minimalist/conceptualist/installationist paradigm of which Debord would himself say forty years later that it had not produced even one work worthy of any interest at all, Debord failing to mention, however, that Hurlements was implicated in that paradigm, and in this sense was a film that, given its contestationist intention, arrived at least forty years too late. It might have been deemed transgressive in…1912 (although perhaps it would merely have been taken as a technical mishap! Maybe it really was!), but in 1952 it was simply the exact contemporary of the exceedingly banal – and careerist – white and black monochromes of a Rauschenberg or of Cage’s insipid 4/11, the itineraries of which represented the height of abjection for both the Letterist and Situationist Internationals and was already historically lagging in relation to Fortuna’s 1946 monochromatic opportunism.

But while there could and can be variation or variability in affective – and even physiological – response to Hurlements or to Wolman’s L’Anti-Concept or for that matter to Isidore Isou’s influential prior film, Treatise on Venom and Eternity (with its initial and sporadic contest of one’s auditory faculties by various voices pronouncing Letterist sound poetry), no physiologico-optical variation is possible when in the presence of Richter’s De Young Museum C-print.

Nonetheless, there will be those who delight in this work for precisely this reason, but they won’t be those who are looking at the work or they will be those who enjoy physiological distress. Partisans of the work will say – in the ubiquitous theoretico-curatorial ideologisms – that the work fulfills perfectly the function of any necessary advanced art, that it has taken upon itself the zeal of artistic and “critical” “experiment”, that it breaks the barriers of the present social order’s domination and authoritarian reproduction, that it investigates the tensions of optics and epistemological and ontological borders and limits. But this kind of defense or description could only make a claim of validity–leaving aside for the moment whether these received and pre-fabricated sub-philosophical and crypto-conceptual claims could ever have validity in fact – if it took upon itself a full exclamation that it willingly sanctions the intentional infliction of distress.

The De Young Museum is located in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park. Adjacent to the Japanese Garden and in the vicinity of the Arboretum, it is an amiable enough setting. The lobby exhibition space that constitutes the main floor garners the usual variation of architectural praise. And the museum’s various historical collections could also win praise, perhaps from most. But it seems to me that Richter’s work should garner a warning label in addition to or better in place of the present curatorial card: “Caution: viewing this work will cause physiologico-optical discomfort”.

Moreover, in this lobby there is a steep and exceptionally wide staircase leading to the second floor and its various exhibition rooms. While ascending this staircase, Richter’s work is at one’s back at an angle and at a distance. But while descending this staircase, Richter’s work will be in view or potentially in view. Is the angle and distance such that one will not be subject to the effects and affects of the work even if one glances diagonally and across the distance at the work? Perhaps. Yet, wouldn’t it be wise, just in case, to erect a warning at the staircase too: “Dear Patron: In order to be on the safe side, please do not, while descending the stairs, glance in the direction of Gerhard Richter’s work. Even at this distance, a glance at the work could be potentially harmful to a patron’s successful negotiation of her, his, their descent of the staircase!”

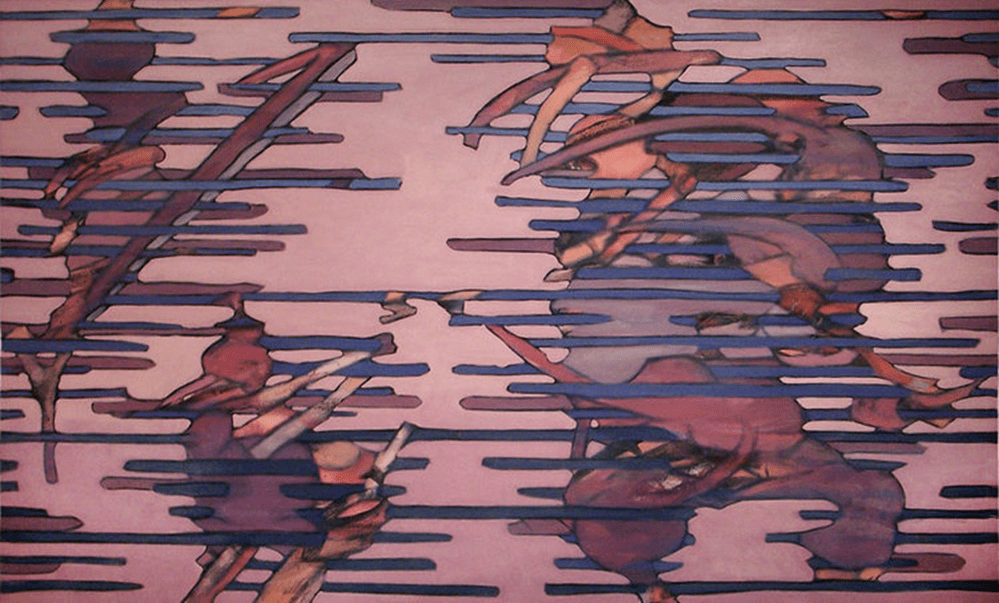

Is it a question here of necessary warning or of easy humor? Like the directive itself says, let us err on the side of caution. But there is an even better instance of humor. And this magnanimous humor is also capable of giving itself to judgments, balancing vehemence with a mirthful (but not derisive) smile, as for example in Alan Silver’s painting, Portrait of Gerhard Richter with Fowl, a delightful moment of play which should not be taken as a send-up of Richter so much as a good-natured and twinkling entreaty, e.g. “O, Gerhard, you needn’t always give the art world the vapidity and pretense that it wants and certainly not now that it will give you everything and more and more in return no matter the quid or the quo – be happy….!” Silver is one of the greatest painters of our time and without question our epoch’s most brilliant and sagacious humorist.

But contemporary art and its world are decidedly in need, not of send-ups – given that this world is absolutely impervious, insofar as contemporary art and contemporary curatorial and art-theoretical reason, etc., are socio-culturally and socio-materially instantiated forms of evermore hypertrophic defense formations – but rather of alarm clock and cure! But a work such as Silver’s portrait of Richter is surely one from which the De Young Museum could gain great benefit were it to adorn the museum’s central space, and all the more because its patrons could all assuredly depart with smiles, not grimaces and frowns!

Benjamin Buchloh has just published a 650-page book on Richter, entitled Gerhard Richter: Painting After the Subject of History (MIT Press, 2024). This essay could be seen as a review of the book.

Bibliography

Agamben, G. “Difference and Repetition: On Guy Debord’s Films”, in T. McDonough, Guy Debord and The Situationist International: Texts and Documents, Cambridge: MIT, 2002).

Bernstein, J. M. Against Voluptuous Bodies: Late Modernism and the Meaning of Painting, Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2006.

Bois Y.-A. Painting as Model, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1993.

Bois Y.-A., and Krauss, R. Formless: A User’s Guide, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1997.

Bois Y.-A. An Oblique Autobiography, Cambridge: MIT Press, 2022.

Buchloh B. Gerhard Richter: Painting After the Subject of History, Cambridge: MIT Press, 2024.

Buchloh, B. Neo Avant-Garde and the Culture Industry: Essays on European and American Art from 1955 to 1975, Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003.

Clark, T. J. Farewell to an Idea: Episodes from a History of Modernism, New Haven: Yale University Press, 1999.

Clark, T. J. The Painting of Post-Modern Life, Barcelona: Quaderns Portatils, 2000.

Clark, T. J. “Gerhard Richter: Grey Panic”, London Review of Books, 33(22), 17 November 2011.

Danesi, F. Le cinema de Guy Debord ou la negativite a l’oeuvre (1952-1994), Paris: Presse Experimental, 2011.

Danesi, F., Levy. E., and Flahutez F. La fabrique du cinéma de Guy Debord, Paris: Actes Sud, 2013.

Debord G. Complete Cinematic Works: Revised and Expanded, ed. and trans. K. Knabb, Oakland: PM Press, 2025.

Devaux, F. Le Cinema Lettriste 1951-1994, Paris: Paris Experimental, 1992.

Du Duve, T. Kant After Duchamp, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1988.

Foster, H. The Return of the Real: The Avant-Garde at the End of the Century, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1996.

Foster, H. Bad New Days: Art, Criticism, Emergency, London: Verso, 2015.

Foster, H. What Comes after Farce? Art and Criticism at a Time of Debacle, London: Verso, 2020.

Fried, M. Four Honest Outlaws: Sala, Ray, Marioni, Gordon, New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011.

Groys, B. Art Power, Cambridge: MIT Press, 2013.

Joselit, D. After Art, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2012.

Krauss, R. The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths, Cambridge: MIT Press, 1985.

Krauss, R. Under Blue Cup, Cambridge: MIT Press, 2011.

Kuspit, D. “Richter D.O.A.”, Artnet, 2002, http://www.artnet.com/magazine/features/kuspit/kuspit2-21-02.asp.

Light, S. “Art, Race, and Jazz: Reply to Barry Schwabsky”, 3 A.M. Magazine, November 2017, https://www.3ammagazine.com/3am/art-race-jazz-reply-barry-schwab-sky.

Light, S. “Museum Curators and Their Public”, Los Angeles Review of Books, January 2017, https://lareviewofbooks.org/blog/essays/museum-curators-public.

Light, S. “Art-Space and Time: On the Visit of the Philosopher and Art Critic Yves Michaud to the Studio of the Painter Alan Silver”, Whitehot: A Magazine of Contemporary Art, November 2019, https://whitehotmagazine.com/articles/of-the-painter-alan-silver/4400.

Light, S. “Naoko Haruta and the Arboreal Imagination”, 3 A.M. Magazine, February 2016, https://www.3ammagazine.com/3am/naoko-haruta-and-the-arboreal-imagination.

Light, S. “The Judgment of Paris”, 3 A.M. Magazine, September 2019, https://www.3ammagazine.com/3am/the-judgment-of-paris.

Light, S. Naoko Haruta: The Supreme Lyrical Intelligence in All Our Painterly Modernity and Contemporaneity, forthcoming.

Osborne, P. Anywhere or Not at All: Philosophy of Contemporary Art, London: Verso, 2013.

Osborne, P. The Postconceptual Condition, London: Verso, 2018.

Osborne, P. Crisis as Form, London: Verso, 2022.

Varnadoe, K. Pictures of Nothing: Abstract Art Since Pollock, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006.

Wolman, G. Défense de Mourir, Paris: Allia, 2001.

Steve Light, a basketball play-making (point) guard following upon Nate Archibald, Pete Maravich, and Willie Somerset–and akin as well to Chris Paul, Steve Nash, Steph Curry, and Earl Boykins–is also a philosopher and poet. His most recent books are The Emergence of Happiness (New York: Spuyten Duyvil, 2019) and Against Middle Passages (New York: Spuyten Duyvil, 2017). Two volumes of essays, Occasions of Happiness: Essays in Philosophy, Poetry, and Painting and To Give Just Weight To All Things: Essays in Politics, Race, Society, and Culture are in preparation. A volume of philosophical aphorisms and essayistic paragraphs, In All Expectation, is in progress and two other volumes, Jean Grenier: A Philosopher Of Light and Shadow and Montaigne and Death, are undergoing revision. He is also the translator of Jean Grenier’s Les Iles (Islands: Lyrical Essays [Los Angeles: Green Integer, 2005]). His writings have appeared in multiple countries on every continent save (!) Antarctica.