The twenty-third album by Habibi Funk Records was released on the 14th of July 2023. But it may as well have been the 14th of July 1973, another summer day in warm Beirut. The album is titled Marzipan and was produced by Lebanese multi-instrumentalist Charif Megarbane. The sound of the album is heavily influenced by musicians from the twentieth-century Arab world, such as Ziad Rahbani, Ahmed Malek, Issam Hajali, and Sharhabil Ahmed. The sound is analogue, the electric guitar is fuzzy, the drums and bass are warm. Again, the new sound of 2023 is nothing else than the old sound of 1973.

The past that we have never experienced exists for us only as something virtual and ghostly. But then, what does it mean when the past of another space, different from ours, for example, that of the Arab world, is returned to the present?

When the past is no longer, it is space as such that remains instead of nothing. One feature of the song titles in the album is, in fact, the reference to a spatial dimension: the market in Beirut (“Souk El Ahad”), a restaurant in the Lebanese countryside (“Chez Mounir”), a hotel on the Mediterranean coast (“Portemilio”). Moreover, the last song title, “Bala 3anouan,” may be translated into English as “without address.” The past returns to the present even though there is nothing any longer to return to.

As Mark Fisher wrote in an article published in Film Quarterly, “The disappearance of space goes alongside the disappearance of time: there are non-times as well as non-places.” And as he also remarked in Ghosts of My Life: “The struggle over space is also a struggle over time.” The album by Charif Megarbane is the sound of a lost future. It is the struggle for a space that is slowly cancelled. I wonder, therefore, how long will it take until a new shopping centre is designed in place of the old market in Beirut?

Fifty years ago, in 1973, Lebanon was economically prosperous but was going through increasing internal tensions that would eventually lead to civil war in 1975. The satirical music of Ziad Rahbani, one of the aforementioned influences of Charif Megarbane, had great success during that period. In contrast, Charif Megarbane’s music is wordless (although, every now and then, there is a humming “bom bom bom” in the background). For forty-two minutes, there are only the sounds of music and the song titles from another place and another time.

Like Western music, the music promoted and distributed by Habibi Funk Records represents the nostalgia for a past that no longer exists. The remastered and mixed ghosts of Habibi Funk, however, are no longer from a past that once was present and represented but that, rather, always exists “beyond all living present,” as philosopher Jacques Derrida wrote in the exordium of Specters of Marx, “before the ghosts of those who are not yet born or who are already dead, be they victims of wars, political or other kinds of violence, nationalist, racist, colonialist, sexist, or other kinds of exterminations, victims of the oppressions of capitalist imperialism or any of the forms of totalitarianism.” In regard to Habibi Funk Records, the spectres are again those of nationalism, racism, colonialism, and sexism; Arabic hauntology is, by definition, postcolonial.

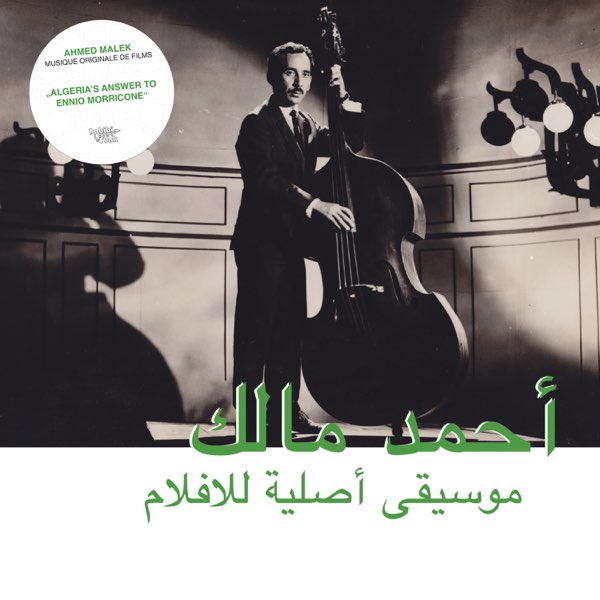

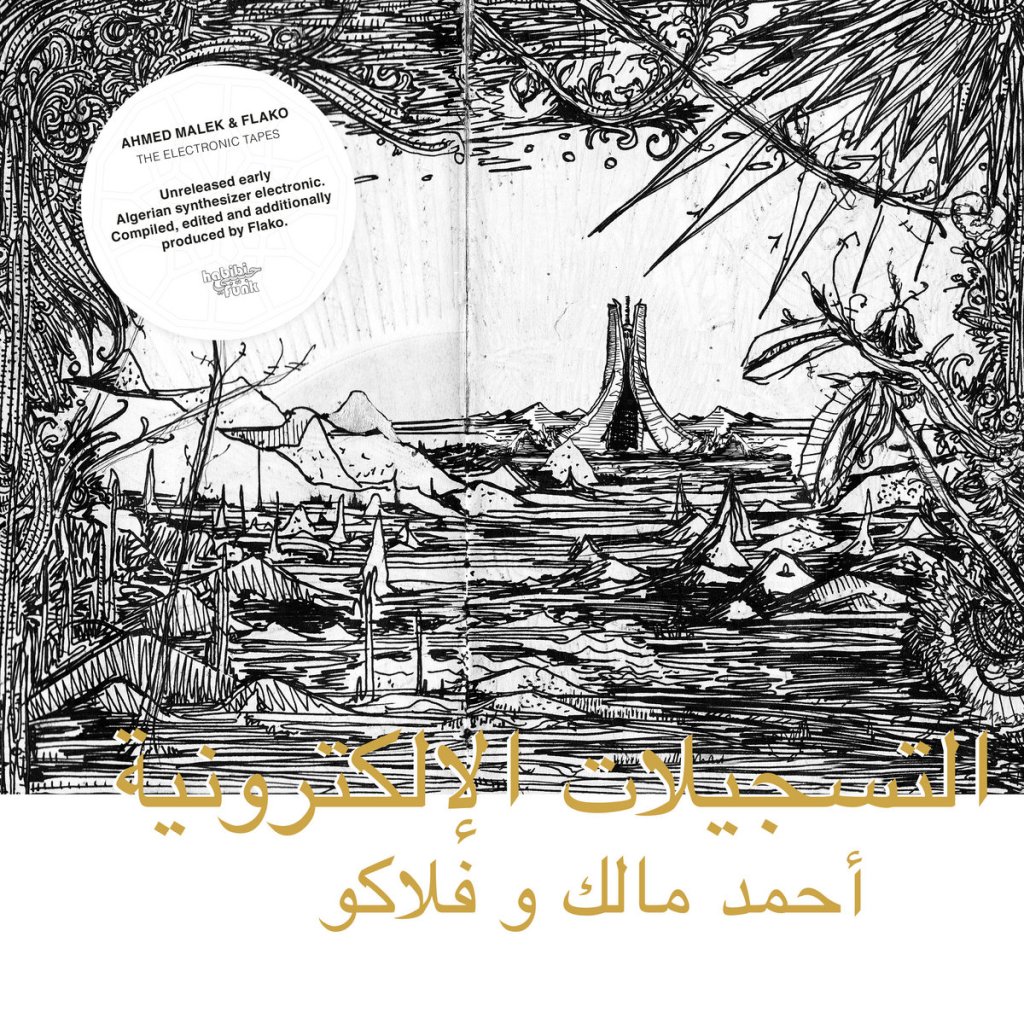

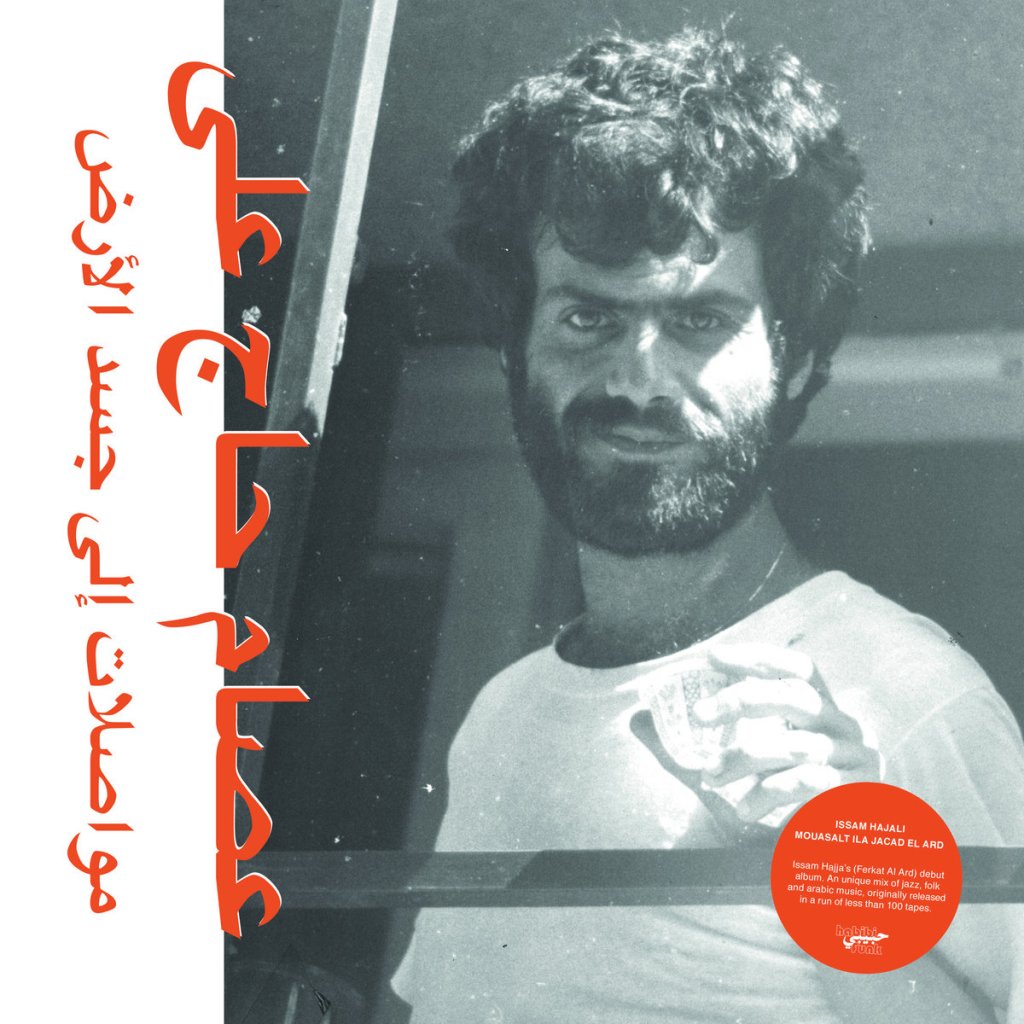

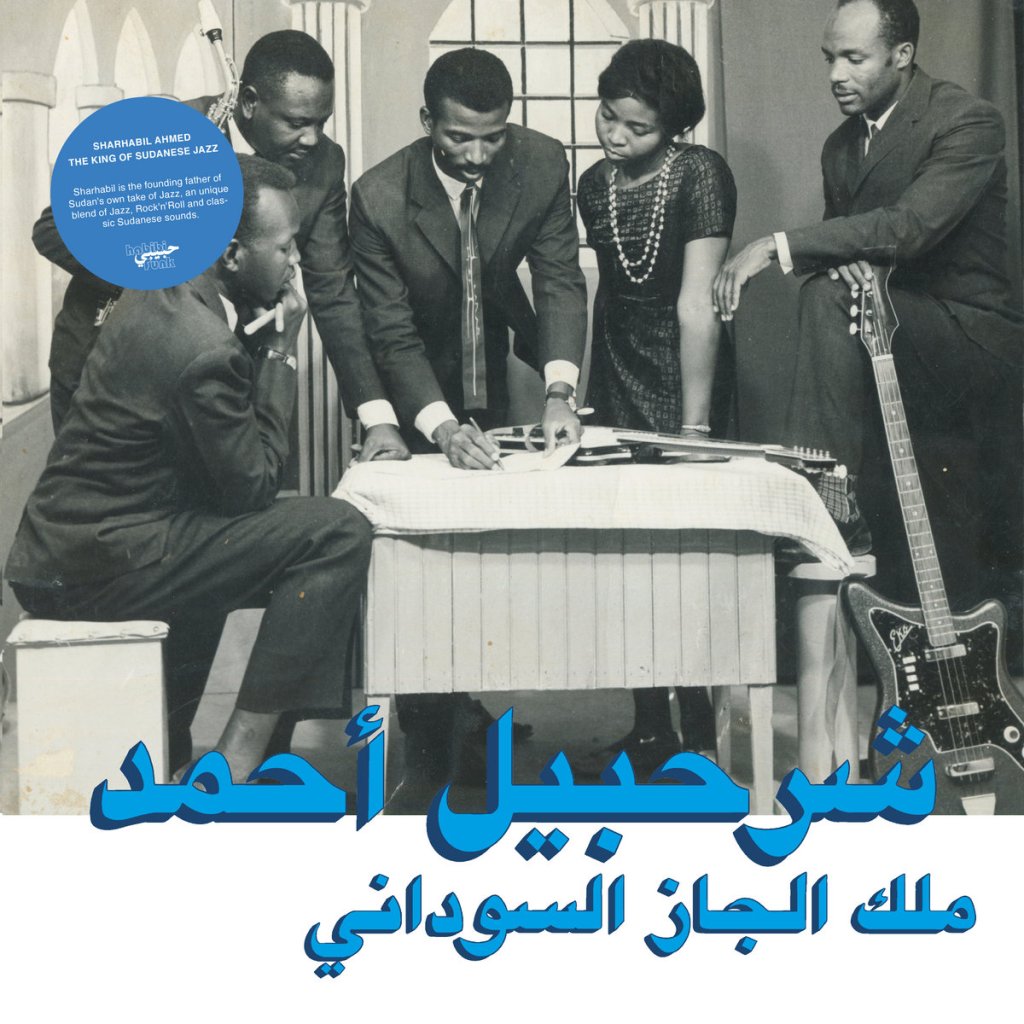

Since 2015, the record label co-founded by Habibi Funk, pseudonym of Jannis Stürtz, focused on the reissue of music from the Arab world of the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s. Based in Berlin, Habibi Funk Records has released music from Algeria, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia, and Sudan, among others, through the years. Furthermore, between 2016 and 2020, Habibi Funk Records reissued the music of three major Charif Megarbane’s influences: two albums by Ahmed Malek (Musique Originale de Films and The Electronic Tapes), one by Issam Hajali (Mouasalat Ila Jacad El Ard), and one by Sharhabil Ahmed (The King of Sudanese Jazz). The songs on Charif Megarbane’s album are the Berlin label’s very first contemporary release. The ghosts of Ahmed Malek, Issam Hajali, and Sharhabil Ahmed return to the present through the analogue music of Marzipan.

The Arabic hauntology of Charif Megarbane shows how time is not only “out of joint” in the Western world but also in that space that always exists between Western and Arab worlds. In this regard, the non-Euclidean space between these two worlds is none other than Berlin. It is, in fact, Berlin — rather than Beirut, Cairo, Khartoum, or Tunis — the city where Habibi Funk Records is based. It is Berlin the place where the rhythm of the past, present, and future returns. At times, the sound of the music is not even from Beirut any more: the first song begins with a Japanese koto played in the style of “the king of Sudanese jazz” Sharhabil Ahmed.

The question is how to put time back in its place. The other question, even more difficult but always in relation to the first one, is how to put space back in its place. “The world is upside down,” “le monde est à l’envers” in French, would be another translation of the Shakespearean quote, “the time is out of joint” (and further discussed by Jacques Derrida in the first chapter of Specters of Marx).

Arabic hauntology is not just a concept about the ghosts of the past but the ghosts of another world. As Habibi Funk stated in an interview with The Independent, the music of the record label should be analysed in a post-colonial context where unfair and colonialist modes of exchange are displaced, and new economic (and political) relations take form and place. At the same time, the commonplaces of the Middle East are also purified by the culture of images of Habibi Funk Records: no more pyramids, no more camels, and no more sphinxes. There is not even the desert of the present but, instead, a photograph from a private collection and a sea of sound and light. The imaginary is always more than an image, yet it is only when the image of the past is modified that another imaginary is again possible: when the culture of the past is neither past nor present any longer, the present itself can only become something else. The music of Habibi Funk Records is, therefore, not only the sound of the music of the past in the present but what the music of the present, for better or worse, cannot communicate except through the past. When the past will change, the future will no longer be the same.

Habibi Funk Records is the nostalgia for the future. At the same time, the new music of Middle Eastern artists such as Kuwaiti musician Fatima Al Qadiri and Palestinian rapper and producer Julmud is already the sound of another future. The future is already starting. Listen, for example, to the song “Falnukmel فلنكمل”, the first single from Julmud’s album Tuqoos | طُقُوس.

As a reviewer put it, “Freedom exudes throughout Tuqoos, evading genre categorization with the practiced ease of an artist who’s lived his life navigating borders.” In Palestine, space and time have been out of joint since 1948. But the music is changing. In contrast with the past-oriented sound of Arabic hauntology, the future of Palestinian music is starting again. The ghosts of the future return to the Arab world. The digital medium reproduces the sound of another space and time that did not exist yet into the present. It is what Matt Bluemink referred to in a series of articles as anti-hauntology, meaning a new sound that is against hauntology as much as it is after it.

The word falnukmel (فلنكمل) in Arabic is translated into English as “let’s continue.” If the sound of Habibi Funk Records is the sound of a lost future, soon enough we will have to say let’s go on.

Bibliography

Bluemink, M. (2021). Anti-Hauntology: Mark Fisher, SOPHIE, and the Music of the Future. Blue Labyrinths.

Derrida, J. (1994). Specters of Marx (trans. P. Kamuf). London: Routledge.

Embley, J. (2018). Habibi Funk: The Label Dedicated to Reissuing Stereotype-Busting Sounds From the Arab World. The Independent.

Fisher, M. (2012). What is Hauntology? Film Quarterly, 66(1), 16–24.

Fisher, M. (2014). Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures. London: Zer0 Books.

Gui, J. (2022). Julmud, “Tuqoos | طُقُوس”. Bandcamp Daily.

Shakespeare, W. (1954). The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. London: The Folio Society.

Alessandro Sbordoni was born in Cagliari in 1995. He is the author of Semiotics of the End: Essays on Capitalism and the Apocalypse (Institute of Network Cultures, forthcoming) and The Shadow of Being: Symbolic / Diabolic (2nd edition, Miskatonic Virtual University Press, forthcoming). Alessandro is an Editor of Blue Labyrinths and the Italian magazine Charta Sporca. He lives in London and works for the Open Access publisher Frontiers.